For nearly two thousand years Mary Magdalene had an identity crisis. It took two millennia for the scholars to remove the stigma of “prostitute” from her name. This, despite the numerous references to Mary in the gospels that indicate she was a person of some significance and a close associate of Jesus. Nevertheless, the scholars could not decide if she should be identified with the unnamed penitent woman who washed Jesus’ feet and anointed them with precious oil (Luke 7:36-50) or with Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus (Luke 10:38-42; John 11:2). It was just a few decades ago that scholars finally agreed that Mary Magdalene could not be identified with either of these women.

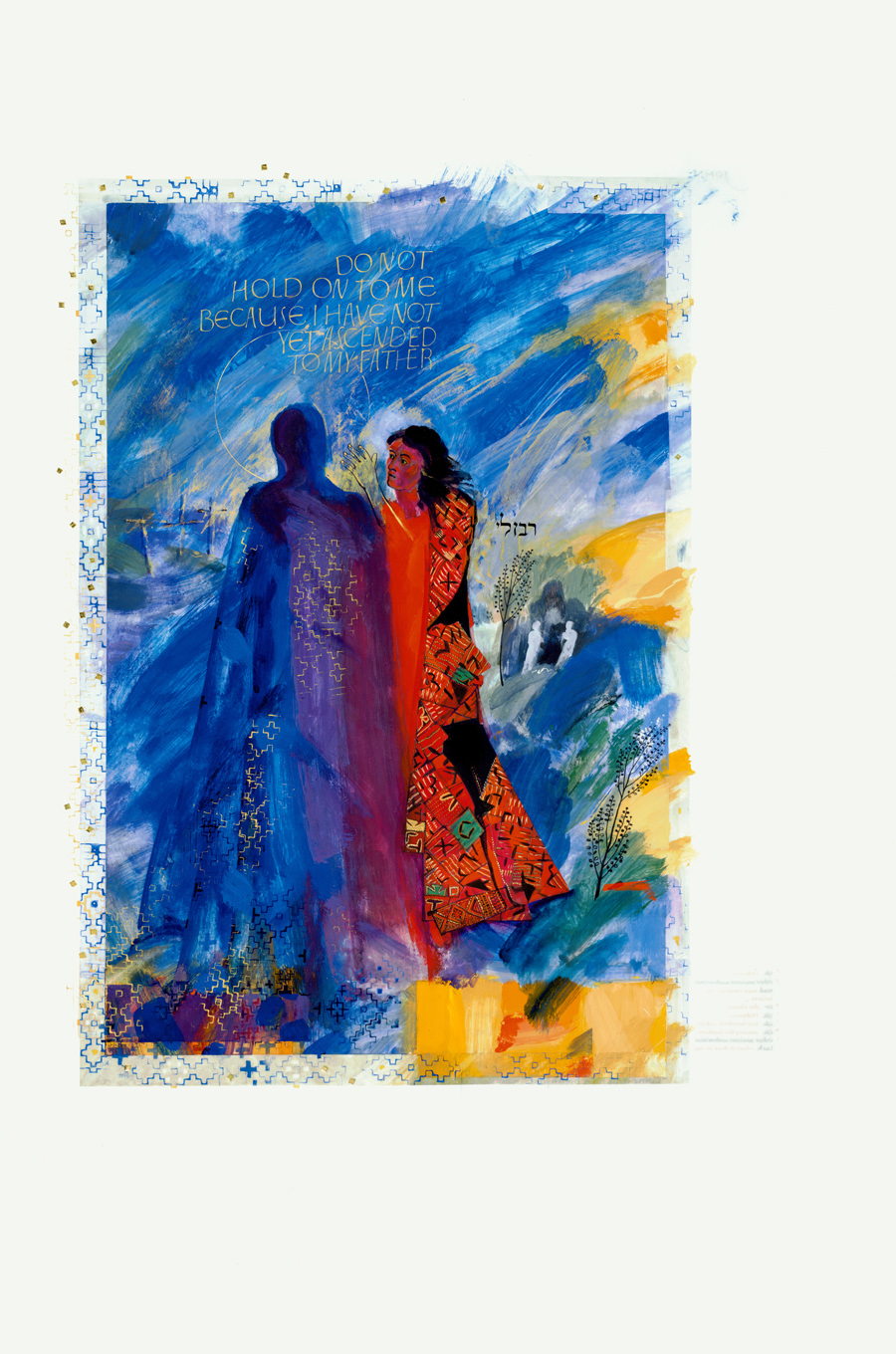

The iconographic history of Mary Magdalene illustrates her identity crisis. For most of the Middle Ages she was portrayed as the “sinner” of Luke’s gospel. Second only to her portrayal as a foot-washing prostitute are the icons of Mary encountering Jesus in the garden after the Resurrection. In these portrayals Mary is always shown kneeling on the ground, sometimes reaching out to Jesus from a short distance, sometimes grabbing his feet. Jesus is always shown with his arm extended, and his hand in a gesture that indicates Mary should remain at a distance from him. This portrayal is the artists’ interpretation of Jesus’ command, “Do not touch [ἅπτου] me.” In Giotto’s fresco, for example, Jesus’ body is ethereal, heavenly, therefore untouchable. But Mary’s body, clothed in a semi-transparent, red, sensual robe, is very earthy. What is not indicated is any sense of physical intimacy between Mary and Jesus.

The Greek word used in the Gospel account, ἅπτου, can be translated “to touch” but also “to embrace.” Consider the fact that the gospels explicitly state that Mary Magdalene was at the Crucifixion, that she was at the tomb after Jesus was buried, and that all four gospels record that she was the first person to whom Jesus appeared after the Resurrection. Clearly, there was a very special relationship between them. Is it too much to claim it included embraces? Would physical intimacy with a woman still be in keeping with his dual nature? Would Jesus, like us in all respects except sin, reject an intimate friendship with a woman?

The Saint John’s Bible, in its depiction of Mary in “The Resurrection,” does not think so. Donald Jackson’s illumination shows Mary standing close to Jesus, their robes melding together. Mary gazes intently at him. One can imagine that they are about to embrace one another. It is a strong image of their relationship, albeit transfigured by the Resurrection event. Notice that Jesus waited for Peter to leave before meeting Mary Magdalene. He wanted to share this moment alone with her. There are two pivotal moments in his life: his death on the cross and his resurrection. Mary Magdalene was at the first event and the first to see him at the second. None of the male apostles are mentioned as being present at his death, but Jesus felt strongly that it was important for them to hear about the resurrection from Mary Magdalene. The command, “Go tell the apostles …” has profound implications.

Fr. Wilfred Theisen, OSB, The Scribe copyright, 2016, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, USA. Used with permission. All rights reserved. www.saintjohnsbible.org.