Prologue: The Divine Untouchable

“Noli Me Tangere” (John 20:17) are the words Jesus speaks to Mary Magdalene as she discovers the first evidence of the resurrection, his empty tomb. These words are not only hard to parse but unsettling. God, who created our existence, who troubled himself to come into the world to help us, who three days earlier had invited us into the eucharistic body with him, says: don’t touch. A rather off-putting rebuff. It calls up another biblical moment of distancing, where Moses, in awe, asks to see God, with whom after all he’s been in conversation for quite a while. God says, nope, you can approach only at a distance, “over there” and see me “from the back” (Exodus 33:18-23).

We can’t see an immaterial, infinite God; we can’t touch. Yet we are supposed to trust and love this deity, who claims to have forged a covenant with Adam, Noah, and the Patriarchs and to have sent his Son in a renewed covenant, a bond of eternal obligation and commitment with humanity. Perhaps Abraham had the faith—or recklessness—to leave his country, birthplace, and father’s house to follow this something-or-other we cannot see or touch (Genesis 12: 1-10). But the rest of us might be forgiven a moment of doubt and check out if the Romans are getting any better object-constancy, as the psychologists say, with their pantheon.

As it turns out, the pantheon, or rather its rejection, is one thing “Noli Me Tangere” is about. It is an invitation to grasp the difference between a deity one can see and touch, who can be made within the structures of human existence, finitude and materiality, and a deity who cannot. God appears to Mary and later to the disciples as the human person of Jesus, visible to us. But when he says, “Noli me tangere, I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God,” this is something else, the immaterial Son-God, who is not of the created world. He cannot be seen or touched. Mary, even in an effort to love, cannot physically hold onto him. God must be held onto in some other way called faith.

“Noli Me Tangere” is a reminder of that. The incarnate Jesus was seen, touched, and touched others. After the resurrection, God must be apprehended differently.

But this is prologue and about God. What I really want to look at is the scene in John from Mary’s point of view. What does she—and what do we—learn about humanity?

Tactile Humanity, Fatal Intactness

In the John 20 passage, Mary’s first impulse in seeing the image of Jesus—she has not quite grasped that he is resurrected—is to touch, to make contact. God cannot literally be held onto, but we humans need to touch and be touched. We express relationship through touch, by letting others into our spheres of selfhood, by allowing our intactness to be breached. We hug, caress, shake hands, have sex, put an arm on a shoulder, the whole compendium of physical contact. In turn, contact withdrawn is rejection. A colleague who won’t shake a hand, a friend who doesn’t give a hug, a spouse who won’t share a bed—that’s cutting. It cuts the bond.

We are made for relationships, with God and with each other. This is one meaning of covenant, begun with Adam and Noah and the way of the species since. In biblical tradition, covenant with God and among persons are inseparable: covenantal commitment to others is part of covenant with God, and covenant with God sustains us in commitment to each other. It’s the structure of the Ten Commandments, the first three of which pertain to relationship with God, the rest, seamlessly, to bonds among persons. Attempts to get one relationship without the other gets you the prophets’ ire: Amos is firm on the importance of compassion even over religious rites: “I [God] hate, I despise your religious festivals; your assemblies are a stench to me… But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream” (5:21-24). Proverbs 21:3 reprises: “To do what is right and just is more acceptable to the Lord than sacrifice.”

Whereas God, not in time and world, expresses this entwined covenant divinely, we express it through gestures of the material body Ritual expresses the human need to forge relationship through the senses. As a species, we cannot do without this sensual expression. Children lacking physical and emotional contact suffer cognitive and emotional impairment.[1] Adults who become isolated suffer from increased risk of suicide, higher mortality rates[2] and morbidity, including depression and other emotional difficulties.[3]

So far, this seems a fairly coherent cosmos: each of us is made for covenant at once with God and with persons, a bond expressed by God divinely—“noli me tangere,” “from the back”— and by humanity through our material capacities. A difficulty arises when humanity is prevented from employing its capacities to forge and express relationship. We may be prevented by external forces, such as the covid pandemic, and we may be stopped by internal ones, by our fears of dissolution, should our intactness be breached. And it may be stopped by both, fear of external threat ratcheting up our fear of our unraveling under the physical proximity and emotional demands of relationship.

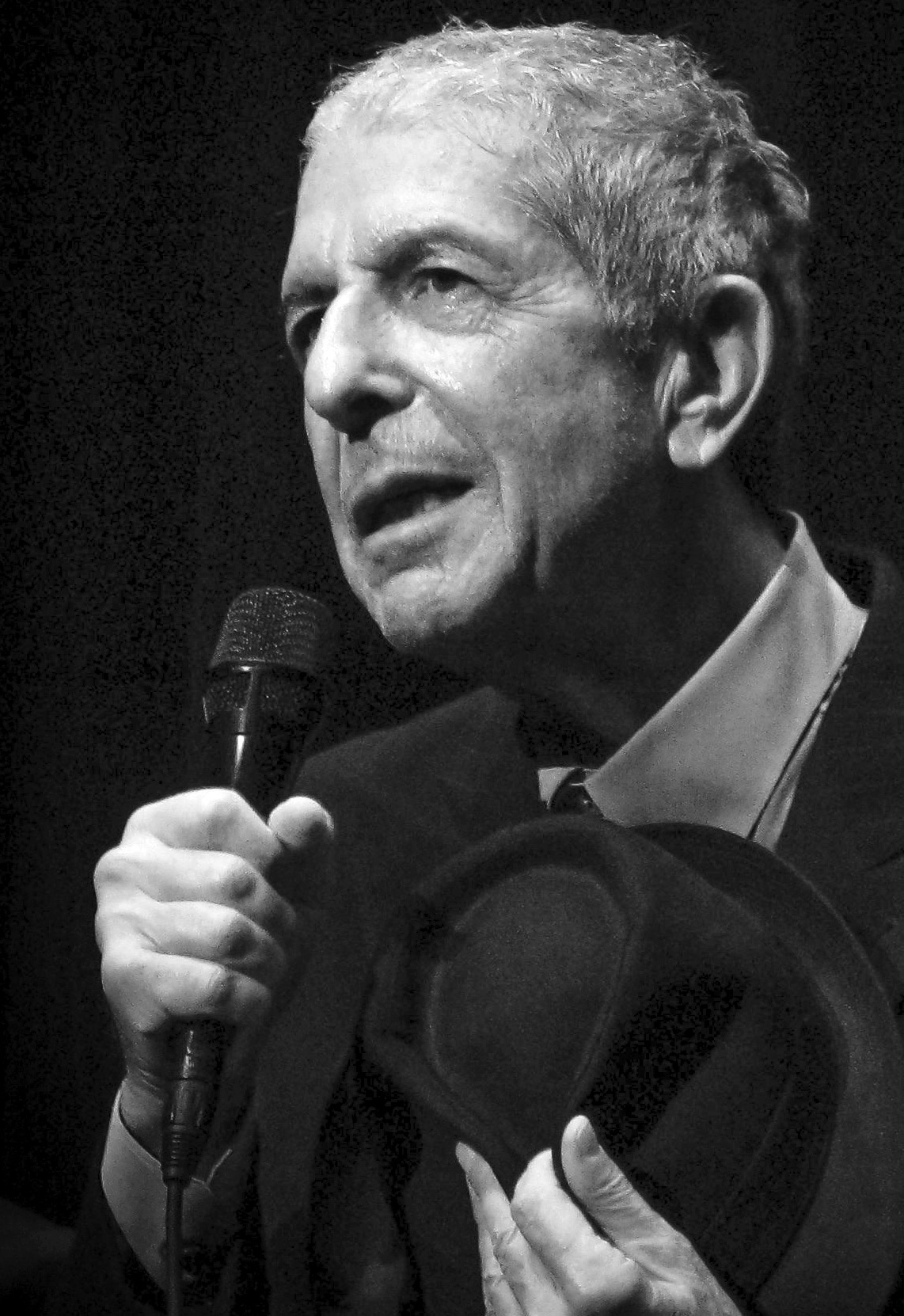

The great rabbi and artist Leonard Cohen had much to say about covenantality and its breaches as he knew himself to be a covenant fail-er par excellence, desirous of relationship with God and others (passionately, with women) and unable to sustain them. Fearful of being subsumed, he bolted. Rinse and repeat, as Babette Babich has said.[4] Here is Cohen in commitment to God: “We are made to lift my heart to you [God]…travel on a hair to you…go through a pinhole of light… and fly on the wisp of a remembrance” to you (“Not Knowing Where to Go”[5]). And here he is in thrall with a woman, from a song that has gripped us since 1967: “And you want to travel with her, and you want to travel blind/And then you know that you can trust her/For she's touched your perfect body with her mind” (“Suzanne”).