As an art historian, my first thoughts of noli me tangere were of familiar artworks depicting the moment of non-touching by Giotto, Titian, Fra Angelico. Mary Magdalene, depicted with her famously bright red harlot hair, seeming to bend under the weight of Christ’s censure not to touch him. It wasn’t until 1969 that Mary Magdalene was rehabilitated from her erroneously ascribed profession as a prostitute – after nearly 1300 years! In the minds of pious Christians, she was seen as the one who should not touch or be touched because of the shame of her impurity. Even though a disciple, she was not perceived as good enough to touch Christ’s holiness. This longstanding perception of inferiority angered me; how horrifically unfair to misunderstand the important work that she was doing!

The Difficult Work of Embracing

by Natalie Oleksyshyn

Mary Magdalene: a passive figure or active agent?

Titian’s depiction of Mary pisses me off. She appears spineless: her body loose, pooling on the ground like the fabric that drapes her body. She is shown as weak and passive, which is antithetical to the important work she does for Christ. She was strong and present when Christ was Crucified. She was present and supportive in the garden after recognizing him, and she was active in teaching and promoting Christ’s legacy.

Perhaps Jesus didn’t mind Mary touching him. In this interpretation, Mary Magdalene was not prohibited from touching, but rather from clinging to Jesus as a human, corporeal life that existed in her lived reality. Perhaps the lesson in this exchange is to accept the continued existence in an unfamiliar form and to help in this transition.

Mary Magdalene: the death doula

I see Mary as a psychopomp, the death doula who takes upon herself Christ’s teachings and shepherds Him through his transmutation from human life in the physical world, to an eternal life as a divine being. It is precisely during difficult moments of ruptured change that ask us to be present, to do the hard work of giving care and stewardship, to support and hold space for the transformation to occur. We are challenged to love even in times of loss and change – to embrace, reassure, and provide strength to one another, to keep moving with the inevitable transformations that we experience throughout our lives. I see Ukrainian women embodying this Mary’s strength.

Ukraine has long been a place from which women were taken. Historian Alice Rio traces slavery raids in the land north of the Black Sea back to the Roman Empire, while Michael McCormic argues that in fact the very origin of the entire European economy was based on the trading of Slavic peoples (Carolingian empire to the Arab world via Venice). Although many of these women’ stories are lost, the strongest example of a Ukrainian woman who was exported from the Slavic lands into the Muslim world is Roxolana (Aleksandra Lisovska, born c. 1505, in Rohatyn, Ukraine).

It is believed that Roxolana was taken in a raid from what is present-day western Ukraine and given as concubine to Süleiman the Magnificent. This story, popularized in history, folklore, and most recently by a famous TV series that ran for six years (1997 – 2003) focused on her rise from a passive sexual possession within the harem to an active participant in the government. Her history of promoting the arts, commissioning many religious and secular buildings, corresponding with other rulers, as well as ascending to the throne and ruling alongside the sultan is well documented. In fact, she is responsible for launching what some historians call the reign of women in this period of Ottoman history. Her journey resonates with my version of Mary, who like Roxolana, is an actor of substance, strength, and agency.

Unfortunately the trading of Ukrainian women did not stop in the 16th century. In the later years of the Soviet Union and following its collapse, Ukrainian women were often used in the gray zone of eastern Europe as sex workers (sometimes sex slaves), transported around the world in one of the largest and most lucrative human trafficking rings. In the 1990s, Ukraine was regarded as the main source of available women. Countless websites popped up to facilitate the purchase of Ukrainian wives. One-sided questionnaires were designed to prioritize and fulfill Western men’s desires, followed by a transaction form that crudely summarized her [lack of] worth.

There were also trips set up for sex vacations. Paris for the lights, Vegas for gambling, Kyiv for fucking; it’s nice to have one’s options so clearly articulated. In fact, on a trip to Ukraine in winter of 2010, I overheard two men speaking in English about their planned sexual festivities for the weekend as they escaped a dreary New Jersey winter. One pointed me out on the shuttle from the plane to the terminal with excitement in his voice: “You see, even at the airport you can spot the difference [in the selection of women]. This weekend will be great!” I remained silent, but inside I felt a volcano of frustration at their desire to touch and possess the women of my country. I made sure not to allow them to “accidentally” bump into me as we exited the shuttle into the airport – a touch that many women have endured on public transportation. I didn’t want them touching me, or the women they spoke about.

On a separate trip to Ukraine, I was sitting in a terminal waiting for my connecting flight when I heard a woman speaking Ukrainian on the phone. I came up to her and we chatted. It turns out that she was on her way back from the states. Apparently, she met an American man online and a romance was struck, although after coming to visit him, they realized that they lacked compatibility and she was on her way back home. She said that the decision to end the relationship came at the expense of a more economically stable life, but that she was not willing to enslave herself. We chatted with the familiarity that only strangers who meet in airports have: with an intimacy of understanding that we will never meet again. She told me about some of her plans for her life back in Kyiv. She seemed at peace and I marveled at her courage.

Shortly before the large-scale invasion in February of 2022, Putin chided the Ukrainian president for not wanting to uphold the terms of the Minsk agreement. “Like it or don’t like it, it’s your duty, my beauty.” Although directed at president Zelensky, his phrasing was decidedly gendered and violent and aimed at all of Ukraine. The reaction from the art community was swift. Street art across the country cropped up, fighting the idea of Ukraine as being a passive victim. A poster in Rivne depicts a woman shooting a male figure who looks like Putin in the mouth. In Russian script above the woman is the message, “I am not your ‘Beauty’ 2022”. On the battlefield, Ukraine’s military routed the Russian army from the northern territories in quick order.

Among the Ukrainian soldiers are many women. Indeed, an image of a woman has become a symbol of resistance and an agent of active protection: a young Ukrainian female wearing the Ukrainian traditional embroidered shirt and a headdress, standing in front of a Ukrainian Church with a semi-automatic gun in her hand. Ray-Ban sunglasses are perched on her nose. At the bottom of the image is text reading “‘Beauty’ will not tolerate it.”

The emboldened image of the female also took on a religious dimension, as she took on the aspect of a new saint: St. Javelin became the unofficial mascot embodying the spirit of Ukraine’s fight. At first there was some confusion as to this juxtaposition between a religious figure and a violent weapon, but in Christian iconography is a long tradition of depicting religious figures with weapons—with the caveat that they be male (St. George and St. Michael are often depicted with swords and spears). Saint Javelin takes her name from the American advanced anti-tank missile launcher that has been central to Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. This saint has essentially “upped her game,” with this high caliber artillery perched over her shoulder. Her head covering is emblazoned with the Ukrainian tryzub (trident symbol of Ukrainian independent statehood, in use since the eighth century).

“go […] and tell them” — to pass on the truth

The war crimes in Ukraine began emerging at a much faster clip than was evident in previous war coverage, mainly due to President Zelensky’s background in law (degree from Kyiv National Economic University) and broadcasting (as actor, director, writer, producer, and chief executive). The unfortunate reality of war is that many times, although heinous crimes are committed, there is often not enough credible evidence to prove it in a court of law. Sometime in April, I attended a round table discussion at a local law school that was focused on the war. I was unnerved to hear one lawyer’s surprise at the quick acknowledgement of the conflict in Ukraine as a genocide, in comparison to the delay and unwillingness by many law experts to label the atrocities committed in the Yugoslav Wars as a genocide. I credit Zelensky’s jurisprudence for the well documented proof of war crimes and his two decades of experience in broadcasting in how the message was shaped and spread.[1]He understands the structure and driving power of media and the difficulty of telling the truth in a business that often plays fast and loose with truth for profit. The rise of fake news, the lightning-fast dissemination of [dis]information and conniving pundits and commentators who tailor facts with more finesse than the cutters on Savile Row are all part and parcel of the industry that he has successfully navigated. As soon as Ukraine was invaded, five privately owned TV channels and state-owned ones combined into one channel, nicknamed United News. The collaboration was set up as a 24-hour tele-marathon, with each channel getting a designated time slot, with all of the channels broadcasting the same content simultaneously. This collaborative effort continues today and was done purposefully to free up the journalists to do in depth reporting and to provide more coverage of the war.[2] Advertising commercials were replaced with mental health check ins and constant fact checking was reported almost immediately. The Deputy head of Detector Media, Svitlana Ostapa, who tracks disinformation and political interference in Ukraine claims that this was the best way to protect the Ukrainian population from Russian fake news spreading and fanning flames of panic among the population.

As soon as the Russian military was pushed out of Bucha in mid-March of 2022, President Zelensky ordered the military to allow journalists into the city in order to document and disseminate the horrors – to acutely etch the evidence into our minds and make the trauma undeniable.

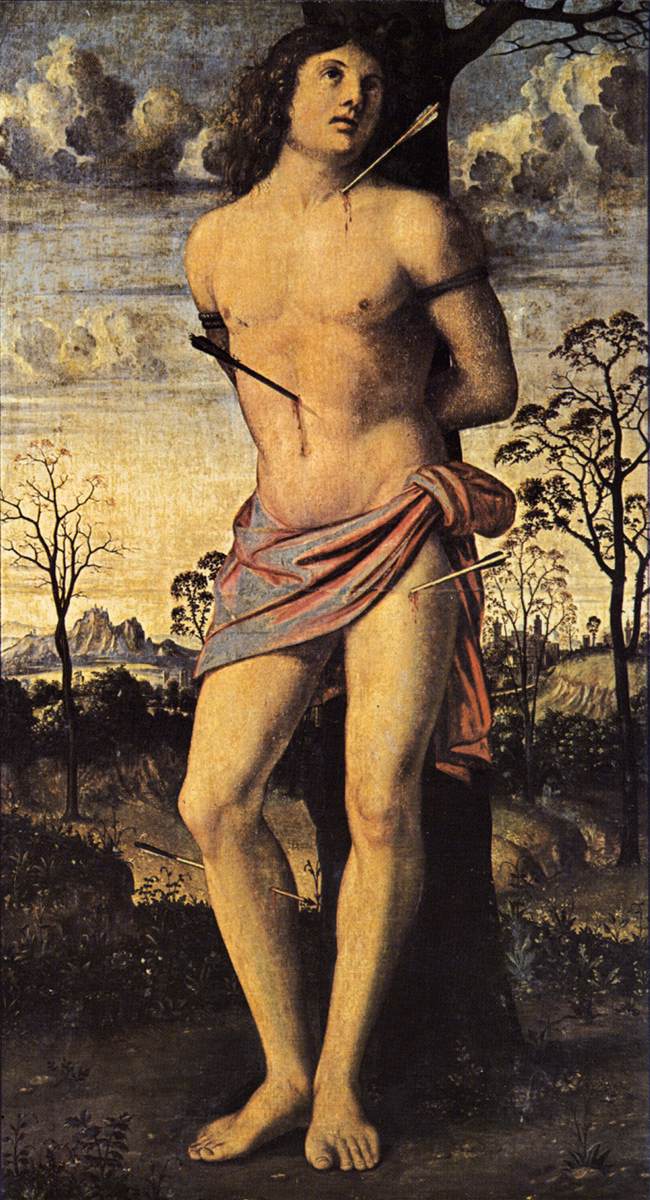

No image of an injured Ukrainian female body was more starkly engraved into my mind than the photograph of a four-year-old girl in Bucha. The body of a dead four-year-old lay on her sister’s body, her hands tied behind her back. The image bears an undeniable similarity to paintings of St. Sebastian, with his youthful nude body contorted in death, the signs of torture still visible. In the photograph, both parents’ bodies were also naked, showing marks of torture, heaped one on top of the other on the left side of the image. Both sisters’ bodies were bound, naked, raped. This photograph documents the still life of Ukraine in the spring of 2022. This image will forever be burned into my memory. It is all that I could see in my mind every time I closed my eyes.

For four days, I walked around trembling, seeing the nude tortured body of this child conveying an anguish that was missing from my art-historical studies of martyrs and other religious figures, whether St. Sebastian or Christ. Christ’s directive echoes through my soul: noli me tangere. No one should have touched that child. I moved around with a low drowning static in my mind punctuated by screams: “No!” “Stop!” “Don’t touch her!” Her: the child. Her: the country. Her: the countless Ukrainian women who have been used and abused.

Spaces of life and death

I thought back to the historical images that I am more familiar with and that are infinitely more soothing than the photographic reportage of war crimes. Curiously, I realized a visual distinction that many artists have often made between the scenes of Christ’s entombment and his sighting by the fiery-haired Mary. The former is typically in a cave, with the landscape usually omitted entirely, closely cropped on the individuals, or dominated by rocks and lacking the vegetation that symbolizes life. The scene of the recognition in the garden is paradoxically alive with life in a vegetal paradise, cocooning the pair as they face each other.

Meditating on the meaning of these spaces gives me hope when I look at the devastating images that get shared on Twitter at 3am EST of Kharkiv, Mariupol, Kyiv. Because beyond the lost lives and suffering, what are these scenes if not the stark tombs that hold death, the crumbling afterthoughts of bygone colonialist spaces? Many of the public spaces that are being destroyed were created during the Soviet regime. I looked at the completely bombed-out square in Kharkiv, modeled on post-Napoleonic city planning, with streets designed with vast empty spaces. Often interpreted as open and freeing, the underlying logic of the spaces was much more sinister, for these spaces were designed to control the flow of pedestrians and quell any riots that may erupt. These spaces were intentionally built to control the people who lived there.

I await the destruction of these spaces with both a heavy heart and bursts of hope and anticipation. The destruction is irreversible — we can never return to the way things were — but the possibility of rebuilding with a different space for the people in Ukraine overwhelms me with excitement.

to make live: see or recognize?

Christ’s death is narrated in John 19:30: the body limp, the spirit gone. But he returned to life in front of Mary. The phrasing “returned to life in front of'' gives me pause. Did Mary seeing Christ bring him back to life or did his rebirth begin at the moment of her recognition when she cries “Rabboni”? Was it the sight of him that made him live again, or was it the recognition that brought him back to life? Is being seen enough to exist? Or does one need to be recognized?

Almost six months to the day since the war began, my rural city of 7,000 residents in Virginia organized to successfully sponsor a family of five to come under the Uniting for Ukraine two-year refugee parole program. As a native Ukrainian speaker, I have been in constant contact with the family—before they arrived, during their trip, and throughout their settling and rooting into this community. I often take them to a local river that has a beach of rocks. The mother sits in a canvas chair next to me and I watch her gazing at her children as they play in the water. The sun glints off their skin and off the water, and the love in the mother’s eyes as she sees her older children helping the youngest, a six-year-old, wade into deeper water. The sight brings a catch to my throat and a pressure to my eyes. The mother talks about the fear of hearing the stories of Bucha as she watches her children, their lithe bodies beautifully moving through the water in the early fall light. She recognizes their safety and their ability to transition to this new place with a community who were all strangers just a month ago. I hear her sigh with peace and see a smile flit across her mouth as the youngest child screeches when a crawfish pinches his finger and the other two gather around to make sure he is alright. Later, we settle at the kitchen table and talk over tea, sometimes sitting quietly while the children’s voices hum from the rooms upstairs. When I leave, we embrace, and as our bodies touch, I am filled with a love and peace that startles me. Sometimes we rock side to side. I feel the light kindling in our souls and spreading to embrace us. I embrace her with a support and love that cocoons and doesn’t impose and helps her decide what is best for her family. I leave to go home assured of their safety, knowing that they are untouchable here.

Our sponsor circle plans a lot and consults the mother often. We listen to her wishes and help bring about whatever change she wants. She is both the subject and agent in this moment of transformation, and I help by embracing the role of doula. The sponsors support them as they grieve losing their country, families, friends and culture and transition to this new life. We are careful not to place any expectations on them, nor do we direct their journey. I support them and recognize their journey. They, like millions of others, are displaced people who are in the process of settling into a different home, different city, different schools, different culture —a different existence. We do our best work in recognizing the difficult process of their journey and embracing them into the community.

[1]https://theconversation.com/ukrainian-propaganda-how-zelensky-is-winning-the-information-war-against-russia-182061

[2]https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/25/death-to-the-enemy-ukraine-news-channels-unite-to-cover-war

Our project takes the words spoken by Jesus to Mary Magdalene in the garden after she discovers his empty tomb — noli me tangere (“touch me not”) — as a provocation for reflection on the COVID-19 pandemic, and on other pandemics, viral and social, that engulf us.