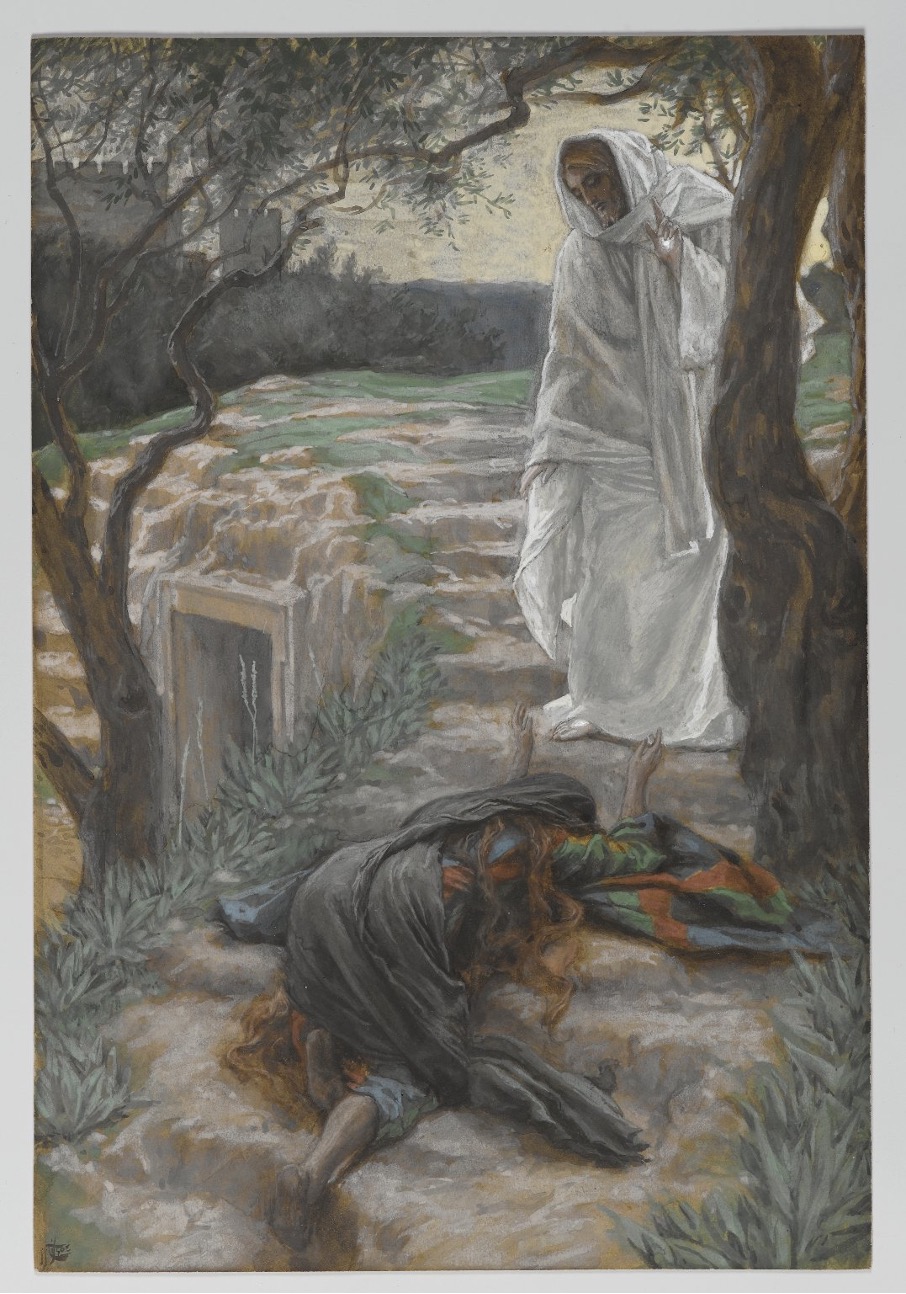

Much that is touching can be felt in the hands and their gestures—Jesus’s hands, for instance, which at once bless Mary and keep her at a distance. Just how touching this visit is can be seen and felt in the space that grows between their separated and separating hands, limp yet longing, outstretched yet losing their grip.

Like Mary, we are touched, gloriously, by what goes away, all the more so by what goes away absolutely. Perhaps nothing touches me more than what touches me by saying, “Don’t touch me, for I am going away gloriously.” Separation touches. This is the logic by which the glorious life of a body appears to touch Mary. It is perhaps the logic of all that touches me.

It was also the truth laid bare by the pandemic’s apocalypse of our world.

A pandemic: it’s everywhere. An apocalypse: the whole world falls apart. There is no place to hide when the whole world is affected.

Surrounded by death, I look for signs of life. Friends, others, anybody whose presence makes me feel life goes on, that these are living times and time still the realm of the living. Is that what Mary was looking for when, grief-stricken, she peered into the darkness of the tomb? Was she also looking for signs of life in the darkness that surrounded her? It seems more likely she was looking for confirmation that Jesus was dead, that death had come upon him and his body rested safely in the tomb, that thieves had not stolen it away. And yet, what she got was the glorious appearance of a body that calls her by her name and speaks to her. What better sign of life? She has had a revelation.

That revelation takes form: it says, “Don’t touch me. Don’t hold me back. I am going on my way to my Father, into the glorious distance of my Father.” That is to say, “Don’t cling to me, for I am on my way to the place from which there is no return.” If there is no better sign of life than this body that speaks to her, what this sign of life might signify is not easy to take. Mary’s revelation is a hard one for anyone to accept: the departure of death does not only surround us in the bodies of the departed, but is also a truth the living carry around with them, each of us, myself, you, and all the others in whom I seek signs of life. The signs of life are the departure whose unknown and impossible meaning has been realized in the bodies of the departed.

This is not a revelation I wanted to have to receive. It is not an easy truth to learn to be in. I did not want the apocalypse disclosing that truth to come so soon. I would rather the secret have remained hidden a while longer. With COVID-times, Noli me tangere came too soon. It’s the truth of all that touches us—that soon it will leave us touched, that soon we will be touched by its leaving. I just don’t want that apocalypse now.

Jeffrey L. Kosky

Lexington, VA, 11 November 2021

[1]My invitation to contribute to this project suggested I reflect on Jean-Luc Nancy’s book,

Noil me tangere: On the Raising of the Body (Fordham UP, 2008) [Originally published in French as

Noli me tangere: Essai sur la levée du crops (Bayard, 2003)]. What I have written is inspired by that book, a book that was written well before the covid pandemic. It is not an explanation of Nancy’s book, but it could not have been written without Nancy’s book.

[2]It is the opposite direction from being-with-others in the world we have in common, as Jesus indicates when he tells Mary Magdalene, who will have been left behind, abandoned, that she should not hold onto him or follow beside him, but go another direction, that is, to the brethren: “I am going to my father,” he tells her, “but you, you go to my brethren and say to them…”

[3]Mary is told, “Don’t hold on to me” after she calls him, “Rabbouni,” a title she would have used frequently to speak with him in the world familiar to her. “Don’t hold on to me,” he says, as if he were telling her not to cling to the world she recognizes and old understandings of the things in it. Rudolf Bultmann emphasizes this point in his commentary. Rudolf Bultmann,

The Gospel of John: A Commentary (Westminster John Know Press, 1971).