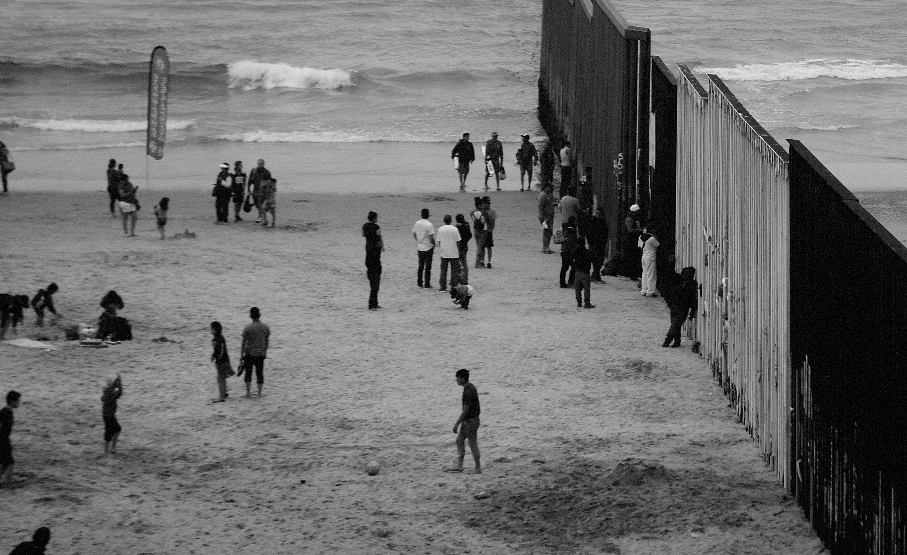

The refugee crisis is a pandemic, and like all pandemics, it is a humanitarian crisis. Rumors or threats of war, actual wars, and other forms of violence have historically forced peoples around the world to move from home-turned-hell toward a place visualized to provide some comfort and safety. The way we respond to the crisis of large-scale human displacements is the same way we respond to the current pandemic, and to all pandemics before it. We look at and treat these crises the same way we treat all our human relationships; we see the problems facing humanity as a problem of us-versus-them. The difference between those we embrace, and those we keep at bay. Those we allow to enter through the walls we build and those we keep out.

A few weeks after the Russian incursion into Ukraine and the exodus of Ukrainians it instigated, I found myself in a conversation about global reaction to the situation. The conversation focused mostly on the West’s double standards vis-à-vis world conflicts and catastrophes. The conversation focused on the alacrity of the Western response to the Ukrainian crisis, both in terms of press coverage and of the reception of Ukrainian refugees. Many wondered: Why was the West so quick and generous in its response to Ukraine when it has been doing everything to block non-European migrants from crossing into its territories? In defending Western coverage of the crisis, CBS News senior correspondent in Kyiv, Charlie D’Agata, said the following a few days after Russian troops entered Ukraine: “This isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European… city where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen.” And a mere day after the widely criticized statement by D’Agata, David Sakvarelidze, a former Ukrainian Deputy General Prosecutor told the BBC: “It’s very emotional for me because I see European people with blond hair and blue eyes being killed every day with Putin’s missiles and his helicopters and his rockets.” Who deserves to be bombed and killed? In the view of D’Agata and Sakvarelidze, certainly not civilized people with blond hair and blue eyes. Who to touch and who not to touch!

The reception of fleeing Ukrainians by European countries was and continues to be as swift and robust as the press coverage of the war. Even Victor Orban of Hungary - the man who instigated a law in his country criminalizing anyone known to be helping asylum seekers, and who had sent troops to stop the flow into Hungary of Syrian, African, Afghan and Iraqi refugees - opened his country’s doors to over 800,000 Ukrainians since the start of Russia’s invasion. At the same time, African students fleeing Ukraine were being stopped at many European borders. Those we let in and those we leave out!

In response to the remarks by Sakvarelidze, a YouTube commentator wrote: “This is why I don't take mainstream journalism seriously. Whatever sympathies I had for the situation has gone out the window. I hope those with dark hair, skin, eyes make it out of there safely.” I can understand the commentator’s frustration. As a Muslim of Black African heritage living in America, I am keenly aware of the discrimination people like me face in the West. Yet, sentiments induced by such Manichean visions of humanity -us and them - shouldn’t push us to replicate them. Two wrongs don’t make a right. We should not let ourselves be blinded to a fundamental truth: that blond hair and blue-eyed people are worthy of our compassion as are dark skin and other non-white peoples.

So, what do I think of the West’s reaction to the Ukrainian refugee crisis? I laud it. Unlike the YouTube commentator, I am truly happy and grateful for the response. Any act of kindness, regardless of the recipient or the giver of it, is a good thing and must be acknowledged as such. What is happening in Ukraine is catastrophic, just like what is happening in Yemen, Ethiopia, and other parts of the world. It teaches us something about the precarity of our existence, that our lives can change for the worse in a blink of an eye. How can one not be moved by the sight of millions of desperate people seeking safety! Including children. Especially children!

Another lesson we can learn from the West’s robust response to Ukraine is that such a response is possible, that we can use our resources swiftly to assist those of us in need. In clear manifestation of our common humanity, in the early days of the crisis, a farmer in Burundi promised to send 240 pounds of his small maize harvest to Ukraine. The farmer, a former refugee himself, described his gesture as a “token of love.” This is a man from one of the poorest countries in the world! Yet, he allows himself to be touched by the sufferings of White Ukrainians thousands of miles away.

Talking about being touched from a distance, I cite another example; this one from my own small community in rural Virginia. Rockbridge County is one of the shrines to the Lost Cause. Yet, in this place where confederates and their sympathizers gather at least once a year to parade their heritage, and where between work and home you endure countless symbols of hate on houses and cars, there are people who have helped strengthen my faith in humanity.

The First Baptist Church of Lexington, a Black church, was one of the first to respond to the Ukrainian crisis by collecting donations for the battered people. I am involved in a local project on hosting Ukrainian refugees here. This is not the first time the community has come together to do something like this. In 2016, when plans to receive Syrian refugees here fell through, the community decided then to welcome and mentor a large Congolese family. As far as the community was concerned, it didn’t matter the color, religion, or national origin of the people in need; what mattered was they were in need. So, the community embraced the Congolese family. Marie, the eldest daughter of that family, wrote this in her college application essay: “When my family first came to America, we didn’t even know how to say ‘hi’ in English. We lived in Lexington VA, for about two and half years. All I can think about that place is how supportive people are to each other. When we first arrived in town, people were so happy to see us. Nobody had to come and see us. Yet, numerous people came to our house. The way they welcomed us was so extraordinary, amazing.” Who do we embrace and who do we push away?

“But Jesus said, Suffer little children, and forbid them not to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven.” Why wouldn’t I want for Ukrainian refugees, children and grown-ups alike, what this community gave to Marie and her family? In fact, why wouldn’t I want that kind of generosity and attention for any group of people in need? We are all, in one form or another, sooner or later, refugees. Or know someone who has been. Each one of us has been and will one day be in need. By helping Ukrainian families, as our community did for the Congolese family not too long ago, we are keeping the hope for a better world alive in ourselves. We are providing a soothing balm to our own soul by sharing with others the love and compassion we need for ourselves.

The Qur’an says: God made mankind into “nations and tribes, so that you might come to know one another.” The most sacred struggle we can undertake is the one in defense of humanity and of human rights. It is the ethical thing to do and we do have an obligation to do it. Given our common humanity and our fundamental and foundational equality before God, we help others not because we think we are better than them. Rather, because we consider them an extension of ourselves: by helping them, we are actually helping ourselves. As Murri artist, scholar and activist, Lilla Watson, has said: “If you have come to help me you are wasting your time. But if you recognize that your liberation and mine are bound up together, we can work together.” We must intervene in human crises not just in the hope of getting something back in the form of material or political profits. We should do so as if our own survival depended on it. When, at the close of World War II, America went into Europe waving the Marshall Plan, it did so in the conviction that America's destiny as a nation and civilization was inevitably and inextricably intertwined with that of Europe. If nothing else links Europeans to non-European peoples, there is the bond of humanity, and this is stronger and more important than any political, economic, or racial self-interest. As Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded us so eloquently in his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail: “I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

In the now discontinued Fox drama, Touch, Kiefer Sutherland’s character, Martin Bohm, suddenly finds himself alone raising his 11-year-old autistic son, Jake, after the death of his wife in the 9-11 terrorist attacks. Jake, who doesn’t talk and shuns physical contact with others, including his father, has a rare gift of empathy that allows him to feel everything, the joy and pain of everyone, everywhere. When he discovers his son’s gift, Martin quits his job and offers himself as the instrument of his son’s vocation on earth, namely, working to maintain the world’s equilibrium. Episode after episode shows the connections between people and events from seemingly disparate cultural, racial, and geographical backgrounds. The show’s creator, Tim Kring, described it as “being ultimately about how our lives all touch one another.” The ambivalence inherent in Jake’s personality and prophetic mission – he doesn’t want to be touched yet is touched and touches everyone – reminds us of Christ’s interdiction to Mary Magdalene: noli me tangere (touch me not). In Christ’s prohibition, as in Jake’s, there is, paradoxically, an invitation to touch.

Touch is only but one of five senses. Those who empathize, like Jake and the great prophets, are endowed with an additional sense. They sense. They feel. That is, they combine all the senses without discrimination. They are the ones who can say: “I feel the other, therefore I am.”

We are beings in need of healing touch. Our fellow human beings are calling on us to touch them. To sense them. To feel them. And we are calling out to them to touch us. Are we, are they, receptive to the call? We hope we are pre-endowed with the ability to feel and then act upon our feeling. For it is only through the mutuality of our touch (or feeling) that we can save our world and, with it, ourselves.