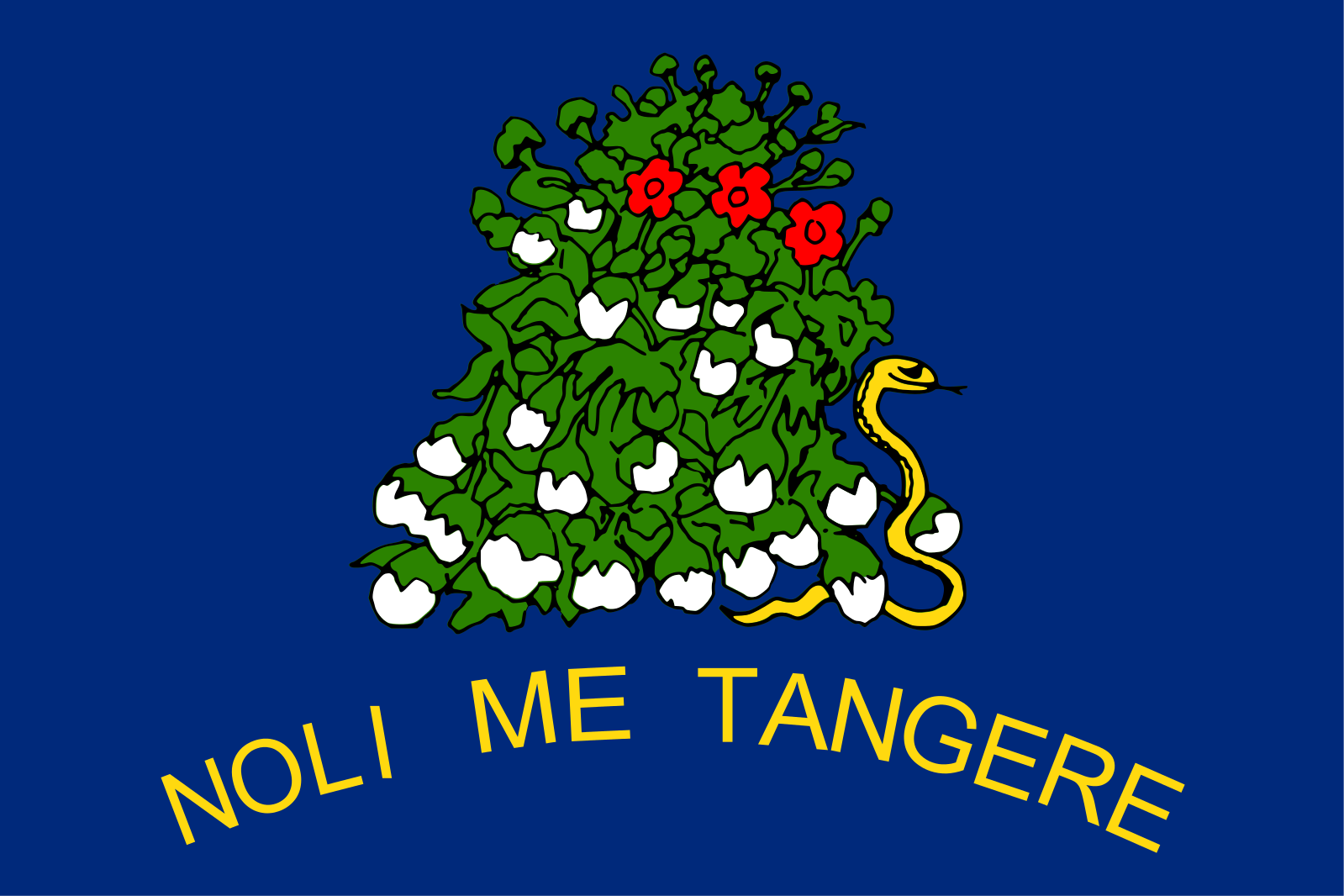

The other side of the flag was more strange. It featured a thick-leaved cotton plant, full of white bolls and three red flowers, with a small yellow rattlesnake emerging from the bottom leaves. Beneath this image were the words Noli Me Tangere.

The flag was a replica of the first secession banner raised in Alabama on January 11, 1861. The original banner was sewn and presented to the convention by a group of Montgomery women, but the Alabama Department of Archives and History says the flag was painted by Francis Corra, who produced many military and decorative banners in Montgomery. The Noli Me Tangere rattlesnake motif was also featured on a flag of the 4th Alabama Volunteer Infantry.

The men at Alabama’s secession convention welcomed the new banner, and raised it above the Capitol. It flew for less than one month before the flag was damaged in a storm and taken down on February 10. The secession banner was never again raised above a public institution in Alabama until 2020, in Albertville.

There, too, it didn’t fly for long. Protestors objected to the display of any Confederate flag. “All of their flags are the same,” explained Unique Dunston, a protest organizer. Speaking to a reporter for the local WAFF television station, Dunston said that Confederate flags meant “division, and racism and white supremacy, and hatred. All of them."

The particular flag in question was in poor shape, with the images on both sides bleeding together. A few days later SCV members took it down and hoisted back up their Confederate battle flag. Protestors responded by renting a billboard.

Today, while the citizens of Albertville remain deadlocked, the brief insertion of “Noli Me Tangere” into their conflict invites reflection. How did the resurrected Christ’s gesture of separation become a motto for secessionists, with an implicit threat of violence? In John 20:17 Jesus’s words to Mary Magdalene suggest a temporary, corporeal division on earth that might precede a more profound, spiritual union in heaven. Is there a similar hope of future reconciliation for the citizens of Albertville? And is there hope for the United States, when the tensions of the pandemic, that have physically separated so many Americans, have also deepened the nation’s political and racial divide? Can healing occur while some Americans cling to the past, never contemplating the full meaning of “Noli Me Tangere”?

*

I’d never seen Alabama’s secession banner until the events in Albertville brought it to light. It was a curious discovery. To the modern eye, a serpent emerging from a Southern cotton plant in 1861 seems darkly appropriate. But it’s strange that no one at Alabama’s secession convention recognized that to embed a serpent within the leaves of their cash-crop might cast an evil shadow over their slavery-based economy. Nor did anyone seem to object that the words of Jesus had been placed within the mouth of a snake.

South Carolina’s secession banner, the “Confederate Palmetto Flag,” also featured a rattlesnake, and apparently the Confederates in Charleston and Montgomery all wanted to invoke the yellow Gadsden flag, designed by South Carolina’s Christopher Gadsden during the Revolutionary War era. In the Gadsden flag a timber rattlesnake appears on a patch of grass, coiled and ready to strike, mouth open with fangs protruding. The snake’s raised tail contains thirteen rattles, to represent the thirteen colonies. Beneath are the words: Don’t Tread on Me.

Today the Gadsden flag is popular among gun-rights advocates and anti-government protestors. It appeared in Charlottesville at the 2017 Unite the Right rally, and during the storming of the U. S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. On rare occasions the Gadsden flag has also been adapted by liberal activists. One incarnation, designed by LGBTQ supporters, features a rattlesnake coiled against a rainbow background.

Benjamin Franklin was the first to promote the rattlesnake as a symbol for the American spirit. In 1754, during the French and Indian War, he published America’s first political cartoon, showing a woodcut of a rattler divided into seven pieces, to represent the colonies’ seven regions. Beneath the fragmented snake were the words Join or Die. Franklin believed the colonies must unite to fight their battles. Survival lay in union.

One hundred years later the people of Alabama used their rattlesnake to support disunion. They invoked Gadsden to promote the secessionists’ cause as a Second American Revolution—a popular Confederate trope. But they missed the whole point of Franklin’s pro-union rattler, while also distorting Jesus’s words.

Franklin and Gadsden both used the imperative mood—the voice of command. So, too, for the Alabama secessionists, who embraced the words of Jesus as the ultimate imperative. But in John 20.17 Jesus’s tone and context are just as important as his words. “Noli me Tangere” contains a brusque note of warning, but no hint of deadly threat. A prohibition can be issued by a loving teacher, or “Rabbouni,” and the most compelling artistic renderings of Jesus’s words suggest tenderness and distance—the ability to communicate love without physical contact.

One of the best examples of this love appears in Fra Angelico’s Noli Me Tangere fresco, from the convent of San Marco in Florence. Fra Angelico’s painting is noteworthy for the gentle sadness in Jesus’s eyes and mouth and he looks upon Mary. Jesus’s hand seems to reach out to her, while the horizontal position of his fingers simultaneously waves Mary off, and his crossed right leg, beneath his robe, steps away from her.

In Fra Angelico’s fresco, Mary Magdalene encounters Jesus on a lawn of white and red flowers, with white representing purity, while red signifies the blood of Christ. The Alabama secession banner uses the same red and white flower symbolism, which was probably influenced by Fra Angelico. Knowledge of European art was part of the Southern planter class’s education, and Francis Corra, who helped design Alabama’s flag, was an Italian émigré who specialized in fresco.

The flowers in Fra Angelico’s Noli Me Tangere are gathered in groups of three and five, to represent the holy trinity and Jesus’s crucifixion wounds, which are painted on Christ’s feet with the same brush strokes evident in the red flowers. The Alabama secession banner includes three red flowers among numerous white cotton bolls, to allude to the trinity and the blood of Christ, as well as the three days of the resurrection. Blooms on cotton plants are often reddish-pink before they produce white bolls, but the flag’s emphasis on three red flowers extends beyond mimesis.

“Noli Me Tangere” might have been a reasonable motto for secessionists, if it hadn’t been combined with the Gadsden serpent. In the months before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Southern states claimed to desire a peaceful separation from their Northern brethren, essentially saying to Lincoln: “Do not cling to us.” But their historical position was never Christlike, despite the Confederacy’s frequent habit of using Biblical rhetoric to try to justify its Cause, and the Gadsden serpent always represented an ironic contrast with the Gospel’s message.

*

Before the Sons of Confederate Veterans raised their secession banner above Albertville, they should have read their Bibles more closely. Then they might have recalled Jesus’s words to his disciples in Luke 10:19, KJV:

Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you.

Jesus was referring to the protoevangelium from Genesis 3:15, in which God promised that the serpent that bruised the heel of woman’s seed would ultimately have its head bruised by that same seed. The Greek translation of Romans 16:20 interprets this bruising of the serpent’s head as a deadly blow: And the God of peace shall crush Satan under your feet shortly.

Julia Ward Howe used the protoevangelium when writing the third verse of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic," originally published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862:

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel:

"As ye deal with my condemners, so with you my grace shall deal;

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with his heel,

Since God is marching on."

So it’s especially ironic to see Americans today, in Albertville and across America, brandishing the serpent’s threat. Luke 10:19 emphasizes that once the Son of Man has been “bruised” in the crucifixion, serpents will be rendered harmless. This was the problem with Gadsden’s flag in the 18th century, and it’s the problem with Gadsden’s serpent-wielding successors.

In the end, the righteous tread on serpents, and crush them.