I grew up in a house where there were many books. My parents, both teachers —educators. We lived distant from the urban centers and the circulations of big ideas in our rural 1970's southern world, but we were near enough that occasionally a book from that world would not only come into our home but take on a talismanic value. Or at least, so I remember it. Perhaps it was only so for me, a child who loved books and who was eager to discover in them what the grownups knew.

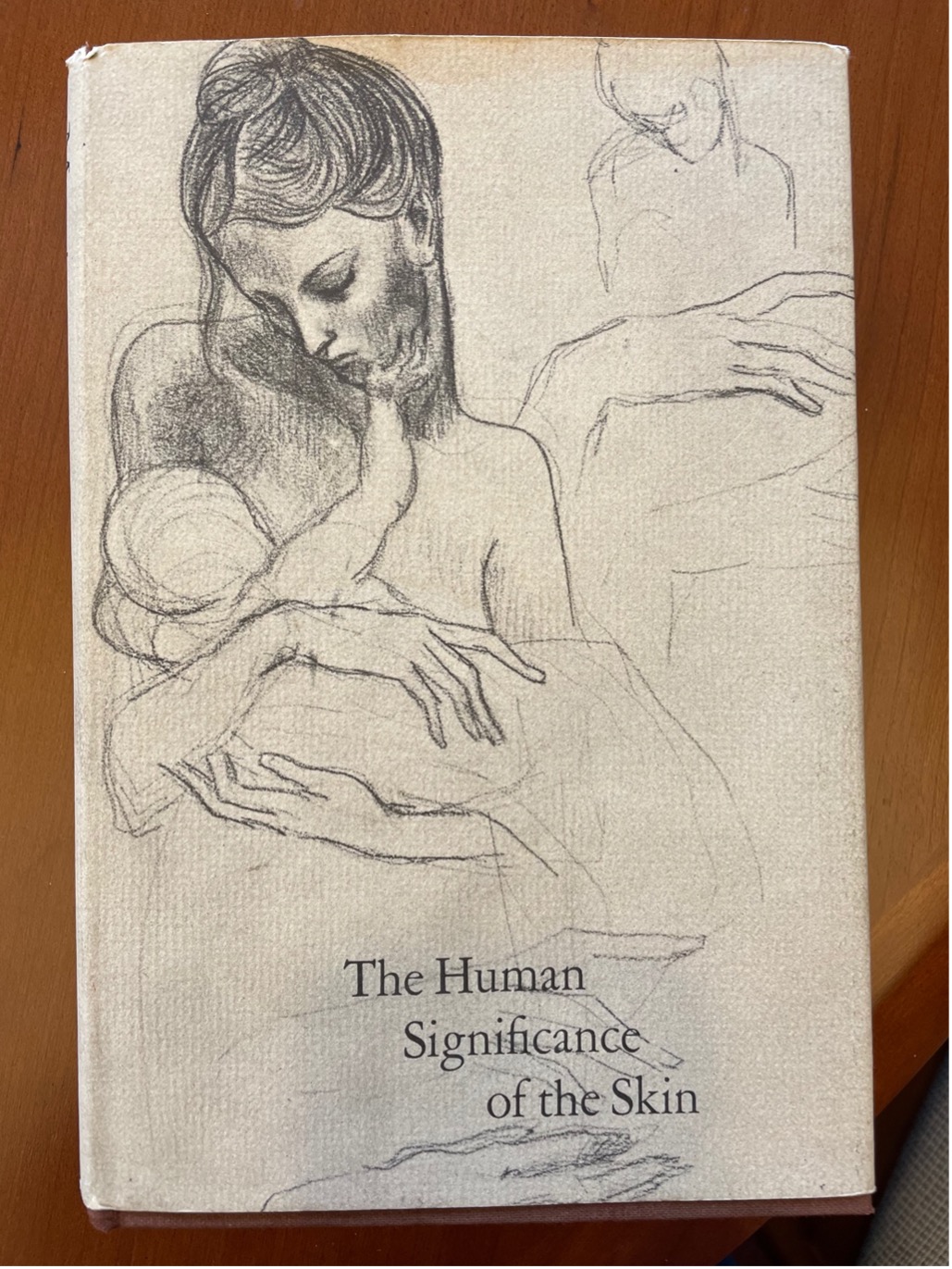

The book Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin was one such talisman. I can see its cover: the sketch of a young mother nursing a child and the red title Touching still there, not yet faded as it has from the copy I now have. The overriding theme of the book is simple and it is captured by the cover. Skin-to-skin touch is essential for human thriving. So, touch your babies and your children, gently and often, especially when they are tiny but also as they grow. Infants need mothers and fathers too — contact, skin to skin. Hold them, cuddle them, bathe them, love them. The skin is the sensory organ that matters most to human development, psychological, emotional, spiritual, intellectual.

How deeply my parents connected with some of its author's outlandish and judgmental theories and half-baked psychoanalysis I cannot say, but I gather not much. The skin of this book makes its message plain, and it was clear to my parents: Please, touch your children, gently, with care, and often, and with love. The physical holding of the child is a form of loving, it is, in fact, perhaps the only way in which a mother can show the infant her love for it. This is equally true for the father or, for the matter of that, for anyone else.

This lesson of the skin is abiding, it is extra to words and to sounds and to sight. It holds its own memory and meaning. I have absorbed this message through my parents' touch, it is perhaps the message that they most clearly conveyed and which remains most uncomplicated to me. Thinking about touch is a different thorny business — altogether complicated and important, fraught, troubled, shaded, disappointing, impossible, banal even. But... How can I put this? My skin and body believes in touch and that it is love.

In my teenaged years, those years when touch inevitably becomes more thought, more complicated, I was still going to church. Every week in Sunday school we would get lost in Bible scenes, falling deep into their crevasses. More than once we would alight on the scene in the garden. In the NIV version that we read Jesus asks Mary not to hold tight to him. It seems in this version that she is grasping and her action takes on a negative connotation. During these bible studies I privately grieved for Mary in the garden. Perhaps I still do, though bible study is many years in the past. I found myself imagining her impulse, the innumerable things that a touch, such a touch, would have conveyed. What has happened?Are you OK. You are present. Should I be frightened. The world will be righted. I am hurting. Whatever has just happened will be sorted out. I love you, I love you. ...

But his refusal made clear that the world was still out of sorts. That whatever was happening, it was not yet finished. And the reader knows — poor Mary — that when it was finished nothing would ever be the same again. The touch in the garden, that was the touch that mattered. That was the one touch that could have put her world back right again. The old world, at least. But not to the new one the testament was announcing.

It remains embarrassing, even now, to think about that scene of intimacy. Even though its interruption is all we see. The interruption is indeed why we see it at all.

If Mary had touched Jesus, would we have the gospel? That is what I have always wondered. In that moment one love ascending, another slipping away.

Touch cannot set everything aright. But the gospel tells us, despite itself, of its power.